R has some extremely useful utilities for profiling, such as system.time(), Rprof(), the often overlooked tracemem(), and the rbenchmark package. But if you want more than just simple timings of code execution, you will mostly have to look elsewhere.

One of the best sources for profiling data is hardware performance counters, available in most modern hardware. This data can be invaluable to understanding what a program is really doing. The Performance Application Programming Interface (PAPI) library is a well-known profiling library, and allows users to easily access this profiling data. So we decided to bring PAPI to R. It’s available now in the package pbdPAPI](https://github.com/wrathematics/pbdPAPI), and is supported in part as a 2014 Google Summer of Code project (thanks Googs!).

So what can you do with it? I’ll show you.

How Many Numerical Operations does a PCA Need?

Flops, or “floating point operations per second” is an important measurement of performance of some kinds of programs. A very famous benchmark known as the LINPACK benchmark is a measurement of the flops of a system solving a system of linear equations using an LU decomposition with partial pivoting. You can see current and historical data for supercomputer performance on the LINPACK Benchmark, or even see how your computer stacks up with the biggest computers in the world at Top 500.

For an example, let’s turn to the pbdPAPI package’s Principal Components Analysis demo. This demo measures the number of floating point operations (things like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division) executed by your compter to perform a PCA, and compares it against the number of operations theoretically required to compute a PCA. This theoretical value is determined by evaluating the different compute kernels that make up a PCA. For an mxn matrix with PCA computed via SVD of the data matrix (as in R’s prcomp()), we need:

2mn + 1operations to center the data.6mn^2 + 20n^3operations for the SVD.2mn^2operations for the projection onto the right singular vectors (theretx=TRUEpart).

We only add the count for centering (and not scaling), because that’s the R default (for some reason…). For more details, see Golub and Van Loan’s “Matrix Computations”.

An example output from running the demo on this machine is:

m n measured theoretical difference pct.error mflops

1 10000 50 212563800 203500001 9063799 4.264037 2243.717

So pbdPAPI measured 212.6 million floating point operations, while the theoretical number is 203.5 million. That difference is actually quite small, and seems fairly reasonable. Also note that we clock in at around 2.2 Gflops (double precision). And we achieve all of this with a simple system.flops() call from pbdPAPI:

library(pbdPAPI)

m <- 10000

n <- 50

x <- matrix(rnorm(m*n), m, n)

flops <- system.flops(prcomp(x, center=FALSE, scale.=FALSE))

Mathematically Equivalent, but Computationally Different Operations

Another interesting thing you can do with pbdPAPI is easily measure cache misses. Remember when some old grumpy jerk told you that “R matrices are column-major”? Or that, when operating on matrices, you should loop over columns first, then rows? Why is that? Short answer: computers are bad at abstraction. Long answer: cache.

If you’re not entirely familiar with CPU caches, I would encourage you to take a gander at our spiffy vignette. But the quick summary is that lots of cache misses is bad. To understand why, you might want to take a look at this interactive visualization of memory access speeds.

To show off how this works, we’re going to measure the cache misses of a simple operation: allocate a matrix and set all entries to 1. We’re going to use Rcpp to do this, mostly because measuring the performance of for loops in R is too depressing.

First, let’s do this by looping over rows and then columns. Said another way, we fix a row and and fill all of its entries with 1 before moving to the next row:

SEXP rows_first(SEXP n_)

{

int i, j;

const int n = INTEGER(n_)[0];

Rcpp::NumericMatrix x(n, n);

for (i=0; i<n; i++)

for (j=0; j<n; j++)

x(i, j) = 1.;

return x;

}

Next, we’ll loop over columns first, then rows. Here we fix a column and fill each row’s entry in that column with 1 before proceeding:

SEXP cols_first(SEXP n_)

{

int i, j;

const int n = INTEGER(n_)[0];

Rcpp::NumericMatrix x(n, n);

for (j=0; j<n; j++)

for (i=0; i<n; i++)

x(i, j) = 1.;

return x;

}

Assuming these have been compiled for use with R, say with the first as bad() and the second as good(), we can easily measure the cache misses like so:

library(pbdPAPI)

n <- 10000L

system.cache(bad(n))

system.cache(good(n))

Again using this machine as a reference we get:

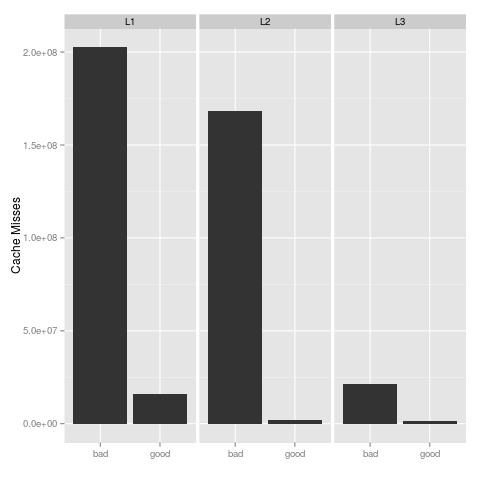

$`Level 1 cache misses`

[1] 202536304

$`Level 2 cache misses`

[1] 168382934

$`Level 3 cache misses`

[1] 21552970

for bad(), and:

$`Level 1 cache misses`

[1] 15771212

$`Level 2 cache misses`

[1] 1889270

$`Level 3 cache misses`

[1] 1286338

for good(). Just staring at these huge values may not be easy on the eyes, so here’s a plot showing this same information:

Here, lower is better, and so the clear winner is, as the name implies, good(). Another valuable measurement is the ratio of total cache misses (data and instruction) to total cache accesses. Again, with pbdPAPI, measuring this is trivial:

system.cache(bad(n), events="l2.ratio")

system.cache(good(n), events="l2.ratio")

On this machine, we see:

L2 cache miss ratio

0.8346856

L2 cache miss ratio

0.112331

Here too, lower is better, and so we again see a clear winner. The full source for this example is available here.

Wrapup

pbdPAPI can measure much, much more than just flops and cache misses. See the package vignette for more information about what you can measure with pbdPAPI. The package is available now on GitHub and is permissively licensed under the BSD 2-clause license, and it will come to CRAN eventually.

Ok now the downside; at the moment, it doesn’t work on Windows or Mac.

We have spent the last month working on extending support to Windows and/or Mac, but it’s not entirely trivial for a variety of reasons, as PAPI itself only supports Linux and FreeBSD at this time. We are committed to platform independence, and I believe we’ll get there soon, in some capacity. But for now, it works fantastically on your friendly neighborhood Linux cluster.

Finally, a quick thanks again to the Googs, and also thanks to the folks who run the R organization for Google Summer of Code, especially Brian. And thanks to our student, who I think is doing a great job so far.